From Mountain Xpress:

The imminent mass retirement of baby boomers has both economic advisers and worker advocates worried about the future of small businesses in Western North Carolina and beyond. Boomers, many of whom will retire within the next decade, own roughly half of all American businesses, census data shows.

This looming “silver tsunami” is unprecedented, says Matt Raker, director of community investments and impact for the Asheville-based nonprofit Mountain BizWorks. Nevertheless, over 85 percent of small-business owners nationwide never get around to devising a succession plan for their company, according to a 2004 U.S. Small Business Administration study.

Ideas about what constitutes a small business vary considerably. According to the SBA, they can include companies with up to $35.5 million in sales and 1,500 employees. In common usage, though, the term often refers to businesses with sales of less than $7 million and fewer than 500 employees.

Regardless of the definition you use, continues Raker, “It’s really important that we make sure we’ve got all the resources and tools in place to help them transition smoothly.”

To this end, local groups and service providers are encouraging business owners to start planning for their company’s next chapter, while simultaneously devising ways to turn an impending crisis into an opportunity for employees to shoulder new responsibilities while building assets.

A growing storm

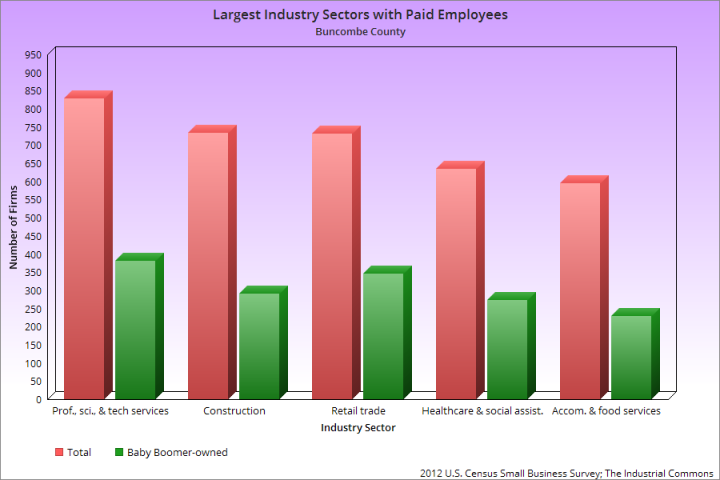

In Buncombe County, 45 percent of all local businesses with paid employees are owned by someone age 55 or older, according to statistics compiled by The Industrial Commons, a Morganton-based nonprofit that supports small businesses and workers’ rights. Using data from the Census Bureau’s 2012 Survey of Business Owners and a template devised by Project Equity, a West Coast sister organization, Industrial Commons has assembled a county-by-county report on boomer-owned businesses in WNC, which the organization released simultaneously with this Xpress article (www.project-equity.org/communities/small-business-closure-crisis/western-north-carolina).

“These statistics are really alarming in some ways,” says Industrial Commons co-founder Franzi Charen, who’s also a member of Project Equity. “Think about how many businesses are just going to liquidate or close their doors, based on the simple fact that the owner’s not planning for succession.”

According to U.S. Census data, the nation’s industry sectors with the highest percentage of boomer ownership are management companies (57 percent), real estate firms (56 percent) and manufacturers (53 percent), the report notes. While Census data doesn’t disaggregate county-level percentages by age, Charen estimates those percentages are congruent to national averages, based on Project Equity’s analysis of available data. All told, boomer-owned businesses account for over 26,000 jobs (out of nearly 60,000 total jobs provided by privately held businesses with employees) and total sales of over $4.7 billion in Buncombe county. Businesses that are publicly traded and non-employer businesses were excluded from the Industrial Commons report.

“There’s a lot of attention about the impact [of aging baby boomers] on the health care system and employment, but we haven’t seen anybody talking about the impact on local businesses,” notes Alison Lingane of Project Equity. Small businesses, she points out, account for half of all jobs nationwide.

But the impact extends beyond immediate employees, says Cindy Clarke, executive director of UNC Asheville’s Family Business Forum. The organization hosts workshops and seminars and helps local family-owned businesses deal with things like succession, planning and general operations. When businesses close, notes Clarke, “The lawyer that handles their stuff loses a customer, as does the bank, insurance company, the accounting firm. It behooves this group of professional service providers to have a support system for family-owned businesses.”

Plan early and often

To avoid this pitfall, most experts agree that succession planning needs to start as early as possible. Some entrepreneurs, says Raker, “start thinking about their exit strategy from day one. The more time you give yourself, the more options you have.”

But knowing how to start those conversations can be challenging, notes Clarke, especially when family members are involved. “It’s hard to have a discussion with your dad about when he’s going to retire or when he needs to let go of the reins,” she points out.

That’s where consultants like John Engels come in. On April 20, the Family Business Forum hosted a special presentation by the nationally known business consultant on how to discuss succession planning with family members and other interested parties.

“The big deal,” he says, “is getting clarity. A lot of other consultants come in with answers, solutions or formulas; I basically encourage open, honest dialogue. What do you honestly want for your company and family? Do you know what you want? Are you willing to listen?”

Involving employees and outside consultants can also bring new ideas to the table, notes Harris Livingstain, an attorney with McGuire, Wood & Bissette. The long-running Asheville law firm is a sponsor of the Family Business Forum. “A lot of business owners don’t recognize that you need that team approach,” says Livingstain, adding, “No one professional has all the information.”

And Richard Kort, Livingstain’s colleague at the law firm, stresses that succession isn’t a one-time event: It’s a process that plays out over time. “You have to make sure your legal documents are up to speed and kept current, which is very uncommon.”

Working for Junior

Handing off the family business to the next generation might seem like an easy solution. But between the early 1980s and the early 2000s, only 15 percent of such enterprises saw that happen, according to a 2004 U.S. Small Business Administration study. That’s down from 25 percent in a previous study. “Kids generally don’t want to take over their parents’ business,” says Lingane. “If that trajectory is continuing, where are we at today?”

Even when there is a potential successor within the family, handing over the reins may be easier said than done. “So often, Dad doesn’t think the child can handle the job,” says Clarke, “but they’re never really given the opportunity to ride the bike without the training wheels.”

For Leah Wong Ashburn, president of Highland Brewing Co., the conversation with her father, founder Oscar Wong, took 16 years to come to fruition. “When Dad opened the brewery, I asked him for a job, and he actually turned me down,” she recalls, laughing. “In hindsight, that was actually the best possible decision for me, him and the company. He wanted me to find my own way.”

After working in an unrelated job in Charlotte for several years, Ashburn returned to Asheville and, at the urging of both her husband and her father, joined the Highland team. But rather than taking on a leadership role right away, Ashburn says she worked in various departments, learning the company’s operations.

Besides ensuring that the successor is genuinely ready to manage the business, this kind of training period, notes Clarke, builds trust among the employee base. “Son or daughter needs to work in all areas of the business and be trained by people who aren’t necessarily dad,” she says. “A lot of times, the owners’ kids have to work the hardest, and it should be that way.”

Involving employees in the succession process can help foster a sense of fairness, says Livingstain, and increase the likelihood that they’ll stay on after the transition. He stresses the importance of keeping employees who aren’t family members happy, “so they don’t feel they’re working for Junior while he’s off playing golf.”

In Highland’s case, Ashburn says staff heavily influenced her father’s decision to turn over the company to her. After considering several possible successors to Wong, Highland’s managers approached him and suggested that Ashburn was the best candidate. “It was the biggest compliment I’d ever received; it still makes me teary,” she says.

Building community

If the business can’t be kept in the family, selling it is the next obvious option. But according to a BizBuySell.com article by author and sales broker Richard Parker, only about 20 percent of such firms succeed in finding a buyer when they’re put up for sale. One way around that is to sell to the existing employees, either through an employee stock ownership plan — which bigger companies like New Belgium sometimes utilize — or converting it into a direct owner-worker cooperative.

Employee ownership “not only solves a problem of succession, it also infuses us with something we’re good at, which is a strong local identity,” says Industrial Commons co-founder Molly Hemstreet, a worker-owner at Opportunity Threads in Valdese. Since its inception in 2009, Opportunity Threads has grown from a single sewing machine to a business with 23 employee-owners and a 10,000-square-foot facility.

Hemstreet sees the impending transition of boomer-owned businesses as a chance to diversify ownership and increase workers’ wealth while supporting the region’s traditional industries. “People have lost pride in any type of work,” she maintains. “One way to regain that pride is this idea of enhancing the relationship with what we spend so much of our lives doing, which is working.”

Converting to employee ownership offers several advantages: Although employee stock ownership plans are more complicated and cost more than selling to a single party, they often give the seller substantial tax deferments, these experts say.

“The business owner doesn’t need to be carrying the flag for employee ownership in order for this to work out,” notes Lingane. “This should just be a good business transaction from the seller’s perspective. It should be able to line up next to other buyers or brokers.”

Such arrangements can also reassure owners that their business will remain in the hands of the folks with the biggest stake in its continuing success. “Often, family businesses also have that family feel for long-term employees,” says Hemstreet. And though they haven’t typically been formally trained in management, she continues, “The employees know how to run it.”

In the case of co-ops, stresses Hemstreet, the idea that they do everything by consensus is a misconception. “It’s not just this floating free-for-all: There’s clear hierarchy and decision-making. Your business works because you meet deadlines and have protocol. You still have to get [product] out the door.” Co-ops also tend to have less employee turnover, making them an attractive solution for rural communities seeking to attract and retain younger folks, notes Charen. “It’s an incentive to say, ‘Hey, you’re not going to have the opportunity to own your own business by moving to a big city, but here’s an opportunity to be a part of something that flourishes into something sustainable, not only for you but for your community.’”

Reinventing labor

In Asheville’s business community, the idea of employee ownership seems to be gaining ground. Workshops hosted by Charen and Mountain BizWorks last year sold out quickly, Raker reports, and The Industrial Commons is focused on educating workers and employers on the ins and outs of transitioning to some form of co-op.

For Sow True Seed, the decision to explore transitioning to an employee cooperative was a good fit with the company’s overall philosophy, says General Manager Angie Lavezzo. “Since we’re focused on giving this product to the people, employee ownership makes sense, because we essentially then will be a sovereign company, owned by the people who care about it,” she explains.

Outside the city, Hemstreet has been working with the Carolina Textile District to further expand the idea of employee ownership among the region’s heritage industries. The Morganton-based network of textile-related businesses connects manufacturers, suppliers, wholesalers and other related entities to help promote and reinvigorate the industry. The organization also offers workshops, resources and training to help textile producers stay competitive and efficient in a global economy.

“People have started asking us how we organize our plants,” says Hemstreet, drawing parallels with the local food movement. “I think we can ride the coattails of that. Now there are tools which can be good for our community and build democracy and, ultimately, a new vision of what industrial workers can see themselves as.”

No single solution

Still, stresses Livingstain, no single solution is a good fit for everyone. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all or fill-in-the-blanks exercise,” he says. “Far from it: It has to be tailored for each and every experience.”

He and Kort advise owners to reach out to community resources such as the Family Business Forum. In June, the organization is hosting a conference that will bring together academics from across the globe to talk about business succession and other pertinent topics. “It’s helpful to hear these different experts from around the world talk about how important it is,” notes Clarke.

In the Southeast, says Hemstreet, employee cooperatives haven’t yet become a popular model, but The Industrial Commons is working with local entities such as the Self-Help Credit Union, Mountain BizWorks and others to provide more resources for people interested in pursuing this approach. She hopes The Industrial Commons’ forthcoming report will drive home to the region’s business owners the urgency of devising sound succession plans.

And whichever model a retiring owner chooses, the transition process should involve the whole community, says Hilary Abell of Project Equity. “As a consumer and a person living in a community, if you stop and think about the different businesses you frequent and depend on, pretty much everyone fits into one of those stakeholder buckets. Everyone has a role to play.”